Is an NDA still valid if no confidential information was disclosed?

NDAs are business contracts where one party (typically an employee, independent contractor, or potential partner) promises to keep secret any confidential or proprietary information disclosed to them during the normal course of business or negotiations.

The key for using this type of agreement is in keeping confidential information secret.

So, if you signed the NDA, but no confidential information was disclosed, is the agreement void?

For the sake of full disclosure up front (no pun intended), there may not necessarily be an answer to this, as it encompasses a number of ongoing debates within the legal community and a complicated web of overlapping details.

But, we’ll do our best here to at least clear things up a little bit and it might be best to start with some basic legal definitions, just to be sure we’re all on the same page.

(Stay with me here. You’ll see later on why these definitions are so important.)

First things first. A contract, so long as it meets the four basic elements of a contract, is a pact or covenant in which two or more parties have had a meeting of the minds, agreed to some terms, and the arrangement has the weight of the law – meaning the law will require that both parties hold up their end of the bargain.

The four basic elements of a contract are:

- Mutual assent

- Consideration

- Legality of Subject

- Capacity

A binding contract is one in which both parties have accepted the terms and conditions and therefore the terms become fully enforceable.

Technically, this can happen verbally, but for the sake of this discussion, we’re only going to cover written NDAs. So, once the agreement is signed by all parties, it becomes legally binding.

Legally binding, by the way, is just another way of saying valid. Keep this in mind.

Performance, for legal reasons, refers to the fulfillment of a contract. So, when the promises made through a contract have been accomplished, or the terms of the contract have been fully completed, the agreement has been performed.

It’s important to note here that if one party performs, the other party cannot terminate the contract until they perform, otherwise they’ll have violated the terms they agreed to.

Now, let’s go back to consideration. For a contract to be binding (or valid) each party must actually gain something.

If one party promises to design something for the other, but they don’t receive anything in return, then there’s no consideration and there’s no legally binding contract. If a written agreement was actually signed, but doesn’t include proper consideration, then its void in the eyes of the law– meaning it’s completely unenforceable.

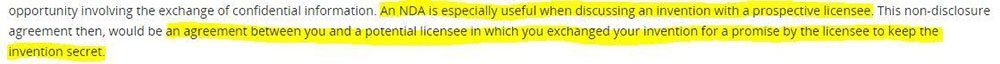

From the experts at Carr Ferrel LLP, this is a great example of what might constitute consideration in a NDA agreement:

In this example above, the Disclosing Party is receiving a prospective license for their invention while the licensee is potentially receiving your business with the promise that they’ll keep your invention a secret until it comes to fruition.

Moving on to our next set of definitions.

If a contract is void that means it’s invalid. It cannot and will not be enforced because it doesn’t meet all the requirements of a contract. It’s null. Illegal. Irrelevant. Unenforceable. Worthless. Choose your adjective.

On the other hand, a contract can also be voidable, meaning that it could be invalidated but is enforceable until the parties agree otherwise, or the court intervenes and invalidates the agreement.

In other words, it’s a valid contract that could be invalidated if challenged or changed.

I feel it’s important to differentiate here between a voided contract and a terminated one. A terminated contract is one that has been legally halted by either party. This must occur before any legal action has taken place and before either party has performed.

This is our last vocabulary lesson, I promise.

An executory contract is one that hasn’t yet been completely performed. So, some part of the promise has yet to be accomplished. Either one party has performed and the other party has yet to complete their end of the agreement, or both parties still need to perform.

Similarly, an executed contract is one in which all of the promises and required actions have been completed – or, the contract has been fully performed.

See how they all intermingle here? Like I said, it’s a complicated web of definitions that constitute the basis of contract law, which is probably why the topic is relentlessly discussed and hotly debated in so much depth.

But, how does this answer our original question? Well, let’s see if it does.

So, you have an NDA that’s signed by yourself and at least one other party.

According to our definitions, you have a binding agreement. You’ve both – all parties involved – agreed to the terms and conditions. For the sake of argument, we’re also going to assume that the agreement has valid consideration.

Typically with an NDA, the Recipient Party that receives the confidential information from you (the Disclosing Party) is providing you some service or other possible benefit in return, e.g. a web app based on your confidential wireframes and sketches.

If the terms of your NDA don’t involve the Recipient Party receiving something of value in return for keeping your secrets, then you don’t have valid consideration.

Likewise, if you’re not receiving anything of value by sharing your trade secrets, then consideration doesn’t exist and your contract is void.

See how we’re making good use of those definitions?!

Dan Shapiro, CEO of Robot Turtles had an interesting take on this matter in an article published by xconomy.com. You can read it here.

So, your NDA is binding, assuming that the consideration is valid. But, is your agreement voidable?

So far, your agreement is enforceable. Even if no confidential information has been disclosed yet, that doesn’t mean it won’t be in the near future and therefore no terms of the agreement have technically been violated.

In the meantime, since no party has performed, it can be fair to argue that your NDA would be voidable. It’s possible that you may challenge the agreement, either by drafting a termination letter or possibly asking for court intervention.

Ideally, your NDA will have a “Termination” clause spelling out your ability to terminate the contract and a simple letter will suffice.

However, as nothing of value has actually been disclosed, no harm has likely been done (at least not for you as the Disclosing Party) and court intervention may be excessive on your part.

In this NDA below, for example, there is verbiage stating that the parties can change the terms of the agreement in writing, if both agree to the changes. It’s possible that you may need to simply write a letter suggesting a change or termination to the terms of the agreement.

![]()

On the other hand, it’s clear that your agreement is an executory contract.

Obviously it has yet to be executed, as neither party has performed. Because it qualifies as an executory contract, the Recipient party may have remedies available to them. As the Disclosing Party, you promised to provide confidential information, assuming to some benefit of the Recipient party.

If the Recipient really wanted to enforce the agreement, they could theoretically reject your letter of termination, request for changes to the terms, and appeal to the court for an order compelling you to abide by the original agreement – meaning that you would have to disclose what you promised to disclose.

If we look at it that way, your NDA is still valid because the Recipient Party has certain remedies available to force the performance you agreed to in the contract.

As the Disclosing Party, if you don’t plan to disclose any confidential information after signing the agreement, you may need to consider the idea of legally terminating the contract so that the Recipient Party can’t enforce your performance at some future date.

Be careful how you approach this, though.

If, however, nothing confidential has been disclosed simply because it hasn’t come up yet during negotiations or other business dealings, then the agreement is still valid and may still have its place.

If you’re still doing business in some way with the Recipient Party, then it’s possible that confidential information may still be disclosed – even if it’s done inadvertently. It happens. And if it does, you’re going to want that NDA in place to protect your business.

You shouldn’t assume that your NDA is void. What the above actually means for you and your business is entirely dependent on the specific circumstances surrounding your agreement.

If you really want to know where the agreements stands for sure, your best bet may simply be to open up communication with the other party and hash it out. Assuming there’s no bad blood, the other party may be on the same page as you and be willing to renegotiate the terms of the agreement or simply terminate it altogether.

Credits: Icon Lock by Márcio Duarte from the Noun Project.

Nov 16, 2017 | Confidential Information | Non-disclosure Agreements

This article is not a substitute for professional legal advice. This article does not create an attorney-client relationship, nor is it a solicitation to offer legal advice.